The following article was written by Carol Besler for Up Here Business Magazine (Issue number 4, 2024). The article has been reproduced with permission from the editor.

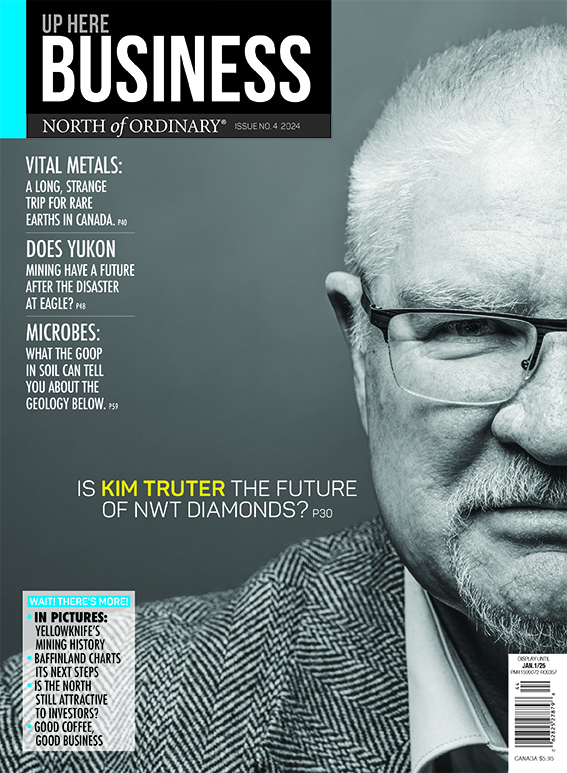

IN 2023, not long after summer had broken out across the NWT, a small company listed on the Australian stock exchange announced it was buying the Ekati diamond mine. That company was Burgundy Diamond Mines, and it was paying US$136 million for Ekati, the first diamond mine in Canada. Kim Truter, the company’s CEO and veteran of diamonds in the Canadian Arctic, was confident about the 25-year-old mine’s prospects. As he would later tell Up Here Business, “We should not have bought the Ekati mine if we didn’t think there was a lot of potential.”

One could be forgiven for finding the timing of Truter and Burgundy’s move hard to fathom. Conventional wisdom says diamond mining in the NWT has reached its sunset years. Production is strong at the moment—it was valued at more than US$1.5 billion in 2023—but that won’t last. Diavik, which has been in commercial production for more than 20 years, is winding down operations and will stop mining diamonds in 2026. De Beers says it will follow suit in 2031, when it plans to shut down production at its Gahcho Kué mine.

And even if those projects weren’t aging, the diamond market has been challenging. Prices for rough diamonds have been in steady decline over the past four years. According to diamond analyst Paul Zimnisky, they tumbled between 15 per cent and 20 per cent in 2023 alone and continued spiraling downward during the first two quarters of 2024.

Prices appeared to bottom out in August and September, but the prospects for recovery are difficult to predict. Industry insiders are pegging the downturn as beyond cyclical, and more structural or existential, a permanent reboot of a once unassailable market. Zimnisky goes so far as to predict, “If we go through three or four more years of decline and the industry’s not making the [marketing] investments necessary, then I would definitely be concerned that the product could really start to lose relevancy with newer generations.”

It’s an extremely challenging time for investing in diamond mining, especially in the high-cost environment of the Arctic. But few people bring as much experience to the diamond-sorting table as Truter.

A 40-year veteran of the diamond industry, the highlights on his resumé include tenures as CEO of De Beers Canada as it was bringing the Gahcho Kué project to production. He was president and chief operating officer of Diavik Diamond Mine. He also served as chief operating officer of Rio Tinto Diamonds, overseeing projects in Australia, Zimbabwe, and Canada, and was managing director of Rio Tinto’s former Argyle mine in Australia, widely viewed as the world’s largest diamond producer by volume.

Moreover, Truter has a confident view of Ekati’s prospects. First, it’s in Canada, a safe and increasingly important jurisdiction for diamond mining now that G7 sanctions against Russian diamonds have come into play. Second, BHP, the company that developed the Ekati mine from the original diamond discoveries in the 1990s by prospectors Chuck Fipke and Stu Blusson, has what Truter describes as the “Rolls Royce of infrastructure.” And that infrastructure remains in excellent condition.

Truter is also confident in Ekati’s resources. The property has more than 100 kimberlite pipes, the host formation for diamonds, and massive undeveloped resources. “One pipe alone is the third-biggest pipe on the planet, Jay pipe,” he says. “We firmly believe that Ekati

could potentially go for another 20 to 25 years.”

Most important, Truter has confidence in his company. “The last time a proper mining company opened this asset was BHP,” he says of Ekati. “When you look at all the subsequent owners, none of them have really been top-drawer miners, and that’s evident in how they’ve tried to develop the asset—or not.”

ACCORDING TO some observers, Truter can be blunt in conversation and his remarks about the history of Ekati’s ownership deserve some fleshing out. When BHP brought the mine into production in 1998, it owned 80 per cent of Ekati, with Fipke and Blusson owning 10 per cent each. In 2013, BHP sold its share for US$500 million to Harry Winston Diamonds, which was then owned by Bob Gannicott, a former junior mining executive who’d played a key role in the discovery and development of the neighbouring Diavik mine with majority partner, Rio Tinto.

Gannicott sold the retail division of Harry Winston to finance the purchase of Ekati and he created a new company called Dominion Diamond Corp., which also held a 40 per cent stake in the Diavik project. Gannicott died of leukemia in 2016 and, the following year, Dominion was sold to The Washington Companies LLC., a conglomerate based in Montana with a primary focus on construction and transportation. Washington paid US$1.2 billion for Ekati, but it would not succeed as a diamond miner. It put Dominion Diamonds into bankruptcy protection in 2020. Arctic Canadian Diamond Co., a firm organized by a trio of

U.S. investment firms representing Dominion shareholders, then bought Ekati in 2021 for $150 million and, last year, sold the project on to Burgundy.

As the mine passed through various hands, different approaches to development at Ekati have been tried. Washington sought to develop the Jay pipe as an open pit mine with a goal of bringing it to production in 2024. Those plans were dropped in 2018, however, as the company turned its focus to an optimization plan to save money. Arctic Canadian Diamond Co. subsequently launched a pilot project to explore the potential of underwater remote mining of previously developed pits that had been flooded.

For Truter, those approaches were not realistic paths to success. “They tried to develop Jay pipe, and it’s quite a technically complex set-up,” he says. “Previous owners placed their bets on underwater remote mining at the expense of everything else… What we’ve done is

we’ve said those opportunities are very much still there, but they’re something for the future.”

Instead, Truter is focusing on a tried-and-tested mining technique called the sub-level retreat method. “It’s quite an inexpensive method from a capital point of view, and it’s a spend-as-you-go procedure,” he says. “There are a few places we can deploy that method on existing pipes around Ekati. And then of course, the open-pit mining method.”

The current project on Truter and Burgundy’s agenda at Ekati is the development of the kimberlite pipe at Point Lake, the location of Fipke and Blusson’s first diamond discovery in 1990. The pipe is home to an estimated 24 million carats (indicated resource), which will

maintain production at Ekati as longer-term strategies are worked out. The most recent mine plan is underpinned by ore reserves of 15.8-million carats, but Burgundy is conducting surface and underground drilling and other work for a new plan, scheduled for release in the first quarter of 2025 that gets the project out to 2030. This will be followed by subsequent iterations aimed at extending the mine life towards 2040.

That potential lifespan has major consequences for the NWT economy. Diamond mining, through its own spending as well as impact-and-benefit agreements, has been a major driver of job creation, tax revenue, and opportunities for business, especially Indigenous business, in the NWT for more than two decades. At its peak, Ekati alone was responsible for 1,800 jobs, including staff and contractors. Even today, it is responsible for about 1,100 jobs, creating a major economic impact that filters through the territorial economy in the form of household spending. Meanwhile, its own spending with NWT businesses stood at $230 million in 2023.

On top of that, notes Paul Gruner, CEO of Tlicho Investment Corp., the economic development arm of the Tlicho Dene First Nation, diamond mining has created a skilled workforce. “Even after the mines close, this can be leveraged in the future,” Gruner says. “There is now a trained workforce available to new mining opportunities coming into the territory.”

Unfortunately, none of the permitted new mines in the NWT are big enough, individually or collectively, to replace the contribution of diamonds to the economy. And that’s assuming they are able to raise the investment to reach production. That’s a hard fact, and Truter signalled it to government and Indigenous leaders in a blunt letter this fall that called for greater flexibility around mining policy, an approach to reclamation securities that doesn’t unduly tie up a company’s capital, faster government valuation of diamond production so companies can get production to market, and assurances that Burgundy won’t be required to renegotiate impact-and-benefit agreements.

The letter found its way to the media and caused a stir. But during his interview for this article, Truter displayed zero patience for the doomsday narrative. “We are not in a fight for survival,” he says. “Having been in the mining industry for nearly 40 years, my experience is that the price of commodities ebbs and flows. It just so happens at the moment we’re in a bit of a low point. There’s no doubt in my mind it will recover.”

As for his letter to the NWT leadership, Truter says, “We believe the diamonds in the North are a strategic asset [and] that the government should be looking at them as a strategic asset… They should be doing everything in their power to make sure the diamond mines continue.”

IF THERE’S one perception about NWT diamonds that Truter wants to push back on, it’s the idea that the mines are closing. “I’ve even heard the terminology ‘a closure industry,’ the concept that the diamonds are now done, and we should now focus on closure,” he says. “I do worry deeply that many people up in the North are almost writing off diamonds, and we’ve got to change that narrative…. Our plan is to focus on the things we can control, like efficiencies and reducing costs and making sure we’re managing the operation as best we can.”

Still, the market remains volatile, and synthetic diamonds—“lab-grown diamonds”—are partly to blame. Grown in factories under high heat and high pressure, they cost a fraction of what it takes to mine natural diamonds, but have the same chemical, physical, and optical properties. The natural diamond industry fights back with various narratives: only real diamonds have resale value; they are rare and finite and thus a true luxury; lab-grown diamonds have a bigger environmental footprint. Still, the fact remains: manufactured diamonds are exactly the same as natural diamonds, at a fraction of the price. It can be a tough sell.

Given the challenge, most industry stakeholders agree that marketing is the key to resuscitating demand for natural diamonds, but that comes at a cost. “De Beers did a very good job of humanizing diamonds, creating an emotional appeal with its ‘Diamonds Are Forever’ and other campaigns,” Zimnisky says. “But the problem is that ever since the De Beers monopoly was dismantled, everybody wants somebody else to pay for the marketing.”

Given Burgundy’s current lean-and-mean business plan, it is not entirely surprising that it does not contribute to the Natural Diamond Council, an organization formed by diamond miners to support generic diamond marketing, a task that De Beers, in its monopoly era, would spend as much as US$500 million on each year. “We don’t have millions to spend on marketing, but we do leverage jewelers that tell the story of Canadian diamonds,” Truter says. “And these days with the advent of social media, you get a much better bang for your buck by using social media to promote using influencers and those kinds of things.”

Burgundy now owns the CanadaMark diamond branding, created by Dominion, and markets diamonds as such through its retail partners. Truter, however, has no immediate plans to cut diamonds in Canada beyond an allotment that automatically goes to the Diamonds de Canada cutting facility in Yellowknife under an NWT government program.

Burgundy does own a cutting operation in Perth, Australia, after acquiring the people and facilities from Rio Tinto when the Argyle mine closed. But Truter says polishing rough diamonds is a tough business. “We select only the highest value stones that can withstand the cost of labour in Australia, but we’re talking about the best of the best and a very small percentage,” he says. “The problem with applying that in other jurisdictions is that we don’t have the infrastructure, and it’s quite an expensive endeavour… There may be future opportunities to do manufacturing in Canada, and we will continue to look at it. But at the moment, that’s not our focus area.”

As for synthetics, Truter acknowledges the problem but takes a dismissive stance. “The natural diamond business is here to stay. People will still get married and follow the traditions, and people still take great pride in putting a natural diamond on their finger,” he says. “There’s a huge bifurcation that’s occurred in the last year or so. Synthetics are now selling in a different market. They’re selling as fashion jewelry at low price points, and they are being sold in fashion jewelry style outlets.”

Moreover, despite their success, prices for lab-grown diamonds have been falling for the past several years. Truter says jewelry stores are increasingly dropping them because there are no margins. In fact, he argues that synthetics have done natural diamonds a favour by highlighting the scarcity of gem-quality natural diamonds and, therefore, their value as a luxury item. “The bigger ones look a bit obvious. If a 20-year-old kid walks into a room with a five-carat, lab-grown diamond, it’s pretty obvious that it’s a lab-grown diamond. So, in many ways, they’ve shot themselves in the foot.”

WHEN THE diamond market recovers, Burgundy is well positioned to further develop the Ekati property and, possibly, even make further capital investments in northern diamonds. It seems likely that De Beers will divest its Canadian diamond assets. Those include Gahcho Kué, which is next door to Kennady North, an advanced diamond exploration project owned by Mountain Province Diamonds, De Beers’ partner at Gahcho Kué. There’s also De Beers’ Chidliak project on Baffin Island.

Truter doesn’t dismiss the idea that Burgundy might be an interestedbuyer. “It actually makes wonderful sense, provided it’s economically viable,” he says. “One of the reasons Burgundy has come into this space is because we see a huge opportunity in the diamond business, the diamond market globally, because there are very, very few players.”

Under Truter’s leadership, Burgundy may in fact be the only company with the expertise and resources to make diamond mining work in the NWT. Operating in remote Arctic environments comes with a host of technical challenges, and Truter has no shortage of experience on that front. More important, though, Truter understands the region and has a holistic view of its communities and governments, both territorial and Indigenous.

“Kim is a driver,” Tlicho Investment Corp.’s Gruner says. “You can spot the people that come in from the outside who don’t understand this world. They either adapt quickly or they die. Kim understands this world. He’s good at it… He’s got real credibility and there is confidence in him. So, when Kim says, ‘Yeah, I think we can do this,’ he’s going to do this.”